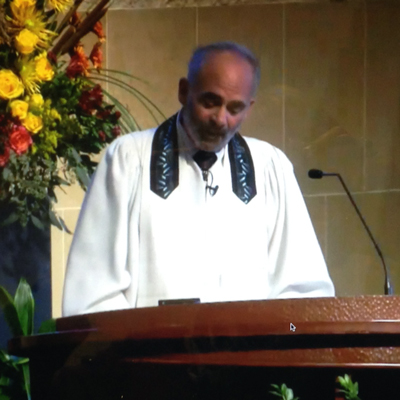

By Rabbi Michael Berk

I thought of my mother a lot this summer. I always think of her at this time because her yahrzeit is the 9th of Av; usually mid-summer. But I also thought of her a lot because the 2016 presidential campaign officially began. My mother is the reason I’m standing before you right now. Among other things, she taught me to love politics and being Jewish. I grew up thinking the two went together. Just as elections are a time to think about the direction our society is going in; so too at this time of the Jewish year everything in our lives is on the table for examination.

My mother was an active Roosevelt – Kennedy democrat, though John Kennedy was not liberal enough for her. She supported Stevenson in 1960, and when Kennedy got the nomination, she walked out of the Los Angeles convention center in protest. But, she returned to San Bernardino to head up “Citizens for Kennedy.” 1960 was the first time San Bernardino County voted democratic in a presidential race. My mom was the first white woman to join the NAACP in our county. She once ran for the school board and lost because in a telephone campaign she was smeared as an “n – word” loving commie. We were always very proud of that.

As for her Jewish life: most of her friends were Jewish; she was very active in and once president of our temple’s Sisterhood and Hadassah. I don’t remember her going to a Friday night service. In our home, Friday night was fast-food night. I don’t remember what we did for Passover. My dad’s shoe store remained open until 9 pm every night between Thanksgiving and Christmas, and since we didn’t see him much during that time, we got our Hanukkah gifts on Christmas morning. When I went to college I didn’t know what Birkat Hamazon or the Talmud was.

But our home was very Jewish.

From my mother I learned that being a Jew had less to do with what I ate than what I said. Being Jewish wasn’t dependent on going to synagogue Friday night but was very linked to working for civil rights. Being a Jew wasn’t just about praising God and hoping to go to heaven, but making the blessings and opportunities of this life and our country more fairly and equitably available to everyone. I grew up thinking that to be a Jew you might observe the Sabbath and holydays; you might keep kosher; but you couldn’t be a racist, and you had to favor the underprivileged.

When our rabbis selected the Torah readings for the holy days, they are telling us what they think is important for us to think about. Our new HHD prayerbook, Mishkan Hanefesh, for the first time, gives Reform Jews the traditional readings for Rosh Hashanah — the story of the birth of Isaac for the first day and the famous Akedah, Binding of Isaac, for the second day.

The story of Isaac’s birth begins with messengers coming to speak with Abraham. Aside from telling him of Sarah’s imminent pregnancy, God also came to tell Abraham what he had in mind for Sodom and Gemorrah. What did Abraham do when God told him He was going to destroy the place? He drew near to God and spoke up and with that changed human history. No human being ever defied a ruler like that and lived. And God doesn’t tell Abraham to shut up! – Who do you think you are talking to me that way? The Torah tells us that God already knows Abraham; He knows that Abraham will teach his children about justice and righteousness. It doesn’t’ tell us God was interested in Abraham because he was an expert in kashrut, nor because he loves God. Lots of people loved God. But Abraham knows that to love God means to do justice and righteousness. That’s why God invited Abraham to argue with Him, the King of Kings.

Jewish Principle number one that my mother understood: religion is not just about rituals and rites performed to make God happy. It goes deeper than that.

After God tells Abraham about his plan for the collective punishment of Sodom and Gemorrah, Abraham says: halila lecha. (v 25) –usually translated as “far be it from you.” While there’s a modicum of chutzpah implied – after all, a mere mortal is addressing God – it sounds very polite. But the phrase in Hebrew is much stronger. The word “halilah” implies a profanation. And it is the root of the word chiloni, secular. Abraham is essentially saying to God: how secular of you! How Un-Jewish of you to kill the innocent along with the guilty!

Do you realize how astonishing this is? The first thing Abraham does after being defined as being good person who will teach the world morality — he approaches the Creator of the Universe argues with Him. That’s the very foundation of what it means to be a Jew. Not keeping kosher. Not observing Shabbat. Not fasting on Yom Kippur. Even way back in the middle ages Nachmanides said you can do all those things and still be a scoundrel. To be a Jew is to be one who stands up and speaks. When Abraham approached God he charted a new course for humanity. Everyone before him is a form of Cain, whose morality was that of a child’s: “Am I my brother’s keeper?” Which is like saying, “I don’t live in world where the existence of others changes my behavior.”

When Abraham approached God and spoke up, he was saying, I am my brother’s keeper. Until that time morality had not developed beyond the principle known as “do no harm.” After Abraham it’s not enough that I don’t harm other people. Abraham takes morality way beyond that. He teaches that our lives are shaped in midst of others.

Principle number two my mother understood: To be a Jew means you have to care about others. You are not allowed to live a life of indifference.

The central story of our Torah is the story of our enslavement to Pharaoh, when God entered history as a Liberator. We are supposed to keep the memory of slavery and redemption before us all the time, and to actually relive the memory of Exodus on Passover. At our Seder tables we tell the shared story of the Jewish people, repeating words each Israelite recited at the Temple when he appeared to renew the covenant on Shavuot.

When the pilgrim gets to the temple, he approaches the priest with a basket of first fruits to offer. He puts the basket down and recites a little speech. He begins, Arami oved avi – which means something about what an Aramean did to “my father” – some distant ancestor. Then he recounts the history of the Jewish people, at least the history the author of Deuteronomy thinks is important: something happened to the ancestor because of the Arameans – we will come back to that. So the ancestor left and went to Egypt. The Egyptians enslaved us, we cried to God and God liberated us.

Arami oved avi: Who was this person, this father from the distant past? And what does oved mean? The phrase has confounded commentators for centuries.

I learned from the scholar Israel Knohl, that “oved” here means a refugee of war. Professor Knohl thinks the ancestor in the verse probably refers in general to the early Israelites. We know that the Israelites first came into Canaan after a horrendous war in the 13th century BCE in the area of Haran. The local population was slaughtered. 1500 people were blinded. It was a very cruel conquest by the Assyrians. There was mass starvation. So, Arami oved avi– there was a group of people who ran away from this cruel war in Haran and came to Canaan. Our history began with our collective parents running away from war.

What happens when you are a war refugee? We are all too aware of this, as Europe is teeming with war refugees now. What is that life like? You have no land; no home; nothing. The history of the Jewish people started by losing everything we had in Haran. Then what happened? We went to Egypt. Again, in Egypt, our status was as the refugee, and the Egyptians ended up enslaving us. We were the “ger” – the stranger; the one who owns no land.

Then the speech of the grateful Israelite begins to conclude: now God has brought us into our own land where we don’t work for others, and we have some measure of security in life.

That’s the history of the Jewish people as the Israelite would recite to the priest, as proscribed by the Book of Deuteronomy. We lost everything; we fled; we were enslaved; we were liberated and given our own land.

What’s missing?

How about a place called Mt. Sinai and giving the Torah. It’s not here. Why not?

Because it wasn’t important to the writer. The point of the confession to the priest is to describe the contrast between the early history of the Israelites and their present situation. We started under terrible circumstances: we lost everything and had to flee for our lives. Now, you are thriving in the Land which the Eternal your God gave you. The author of Deuteronomy knew that when people become the haves, that’s precisely when they need to be reminded what it’s like to be a have-not. The whole ceremony in front of the priest, who surprisingly doesn’t say a word during the entire ritual, was designed, as Passover was, to instill in the heart of every Jew gratitude to God for all He’s done for us. But that’s not the main point.

Because now come the final instructions for this ritual. “… you shall rejoice, together with the Levite and the ger, the stranger in your midst…” You started as a ger, a destitute homeless stranger. Now you have land and prosperity. Show your appreciation for what you have by sharing it with those who have nothing. Now that you are settled and earning a living; you must not forget where you came from; nor those who are now like you were then: gerim, strangers; vulnerable, weak, poor. They are your brothers and sisters. You are no better than them. They will share in your bounty. Invite them to celebrate your holidays with you. You may not be indifferent to them. How could you? You were once them. 36 times the Torah will tell the Jews to love the stranger, the ger – because we were once gerim; and over 50 times the Torah will exhort us to take very good care of the stranger. And as far as Deuteronomy is concerned that’s the main thing you need to know about being Jewish. Even more important than the giving of Torah is to know this – you cannot be indifferent to those around you. You have to care. You must be moral and ethical.

This was an entirely new kind of religion and God. And in the 8th Century B.C.E. something truly remarkable happened in Israel that continued the transformation of religion as the world understood it. The society of that day was cruelly oppressive. A few wealthy and very pious people dominated large numbers of the dispossessed who suffered in great poverty. This wasn’t unusual. Every ancient society was like that; and so are many today. But long ago, in the land of Israel, something unprecedented happened.

A small band of men and women appeared declaring a message that had gotten obscured with the passage of time. While the temple flourished as the ritual center of the nation, and the monarchy grew corrupt, these messengers came to remind the Jews what their religion was supposed to be about. They said that the suffering of the poor was an abomination in the eyes of God. They declared that God wanted people to take religion out of the Temple and into the marketplace, into the courts of law, into the seats of government. The prophets like Amos, Isaiah, Micah and Jeremiah, were meddlers, constantly confronting the rich and powerful of their world.

Isaiah speaks with great clarity that all the pious acts in the world are meaningless to God if they are performed by people with sins on their hands. Your sacrifices? Meaningless, says God. I have had enough of them and take no pleasure in them. Your worship? I can’t bear them. Your festivals? I hate them with all my being, God says. They burden me; I’m tired of them. Your prayers? I don’t even listen to them anymore. Why? Simply put: Because your hands are full of blood. You say one thing and do another. You know what matters to Me, God says: stop doing wrong; learn to do right; seek justice; defend the oppressed; take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow.

What makes you right with God? It’s your relationship to the vulnerable, the stranger, the widow, the orphan, in your midst. The worker, the refugee, the minority, the mentally ill, the aged, those overlooked and struggling. The rituals of the temple provide no assurance of God’s protection. How shallow would that be? No, it is the quality of justice and righteousness in your society that determines the fate of your nation. The fundamentalists say your relationship with God will protect you. And that they know what God wants. But the prophet says that’s not true. Don’t worry about God smelling the sweet aroma of burnt sacrifices going up to the heavens. Worry about those down here who are poor and vulnerable, all for whom justice isn’t working in their favor. Don’t look up; look down. You don’t earn God’s protection through the magical performance of rituals, but by how you protect the unprotected.

My friends, this sermon does not promote a liberal or conservative agenda. I am speaking from my heart to yours about what I think Judaism and our God are really all about. I am talking about what I think is a Jewish agenda for how to order our lives and our communities.

As we think these days of our Jewish obligation to justice and righteousness, and in the weeks to come as we listen to politicians speak about the economy, the disappearing middle class and the growing underclass, the environment, gun violence, matters of peace and war, racism, refugees, women’s health issues, try to ignore the political party, the labels liberal and conservative, all the professed piety. Instead, ask yourself: Is this what a mensch would say? That’s an important criterion; not the only one, but an important one.

You are a son or daughter of Abraham and Sarah. To bring honor to the noble and ancient name Jew, you are supposed to know that the rituals and traditions of your people are not about making God happy, but about reminding you of your obligation to justice and righteousness. God wants more from us than adherence to rules and religious rituals. Rabbi Dr. Jonathan Sacks taught this recently in a weekly essay on a Torah portion with this story: Rabbi Israel of Rizhin once asked a student how many sections there were in the code of law known as the Shulchan Arukh. The student replied, “Four.” “What,” asked the Rizhiner, “don’t you know about the fifth section?” “But there is no fifth section,” said the student. “There is,” said the Rizhiner. “It says: always treat a person like a mensch.”

Sacks comments: “The fifth section of the code of law is the conduct that cannot be reduced to ritual or law.”

Be a mensch. That’s what my mother taught me about being Jewish.